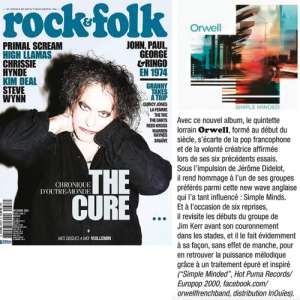

It was the book Themes for Great Cities by Graeme Thomson that inspired Orwell’s frontman Jérôme Didelot to rearrange Simple Minds songs. This biography, which pays tribute to the inventiveness of the early years of Simple Minds, was a revelation to the musician from Nancy: ‘The idea was not to reinterpret songs that everyone had already hummed, but to go and find lesser-known themes in the Scottish band's discography, sometimes drowned out by the radical sound of these early albums, and to offer them in personal, almost solemn versions.

Covering songs… For someone who wants to write, it is the very basis of learning. In fact, a composer's first songs can often pass for covers disguised as originals. Unless, of course, you're dealing with pure precocious talent. For me, it was a laborious process.

I was 14 when I bought myself a bass -although I had never learned music- to start a band with my friend Olivier. I had approached him in the playground a few months earlier because I had been told he owned the Simple Minds’ extended mix EP of Speed Your Love To Me – a rarity in Metz in 1984. Unfortunately, he soon moved away.

Then I was introduced to Stéphane, a high-school student who had a guitar and agreed to perform live with me at a party, accompanied by a drum machine. We worked on five songs: A Forest by The Cure, President Gas by The Psychedelic Furs, Rain by The Cult and two tracks by The Sound, which I loved at the time: Contact's The Fact and Missiles. In the mid-80s, these songs were highly popular with young people like me, who fantasized about the English "new wave", also known as post-punk.

These songs, offshoots of punk music, pure and straight to the point as they were, meant that inexperienced musicians like me could really get to grips with this highly evocative music. Simple Minds were one of the leading bands of the period, yet we didn't dare attempt to cover one of their songs. Because, at the time, there was something very special and unique about this band. Their songs weren't really songs but rather original assemblages born of some alchemy, performed by extremely precise musicians.

Later, when it came to writing my own songs, I tended to look to the undisputed masters of pop tailoring for inspiration (the Beatles, the Beach Boys, Bacharach, Bowie, to name but a few beginning with “B”), turning my back on my teenage idols, even if some of them – Pale Fountains, Prefab Sprout – were in perfect filiation with the great ancients. So I set out on my own path, with Orwell, in an attempt to adapt these melodic precepts to the French language.

But the past always catches up with you. Early Simple Minds records were never far from my turntable, even when exploring completely different territories. (I didn’t really put them forward, as the Glasgow band wasn't exactly influential among the pop aesthetes I hung out with. Then I read Graeme Thomson's Themes for Great Cities. This biography, whose main feature is to pay tribute to the creativity of Simple Minds' early years, was an epiphany to me. The author put words on what had been only diffuse sensations in the young listener I was then.

A few years earlier, I had already recorded a cover of Speed Your Love To Me, just a guitar and my voice. But reading Themes for Great Cities made me realize that I had to go further. The idea wasn't to reinterpret songs that everyone had already hummed, but to turn to the Scottish band's discography and find lesser-known themes, sometimes drowned out by the radical sound of their early albums, and propose more personal, almost solemn versions. As we all know, the music we discover as teenagers is more than just music. Sublimated by a developing imagination, songs that may seem trivial to some can become anthems to others. This is particularly true with Simple Minds, symbolism being essential in the band's early productions (abstruse but evocative lyrics, enigmatic word associations, summoning of the elements...). I then plucked from these emphatic memories a few songs that had almost became others by dint of mental construction, and asked Orwell's historic collaborators (Régis Nesti, Jacques Tellitocci, Emmanuel Harang and Renaldo Greco of course, but also Alexandre Longo and Thierry Bellia) to help me embellish them. "He's so simple minded" sang David Bowie... For sure, simple minds can do great things.

TRACK BY TRACK (by Jérôme Didelot - Orwell)

20th Century Promised Land : Even for a die-hard fan, this may seem a surprising choice, since, as far as I know, this track has never been played live by Simple Minds. I've always thought that its chorus, which takes a while to appear, was one of the best the band produced at the time, not necessarily highlighted in the original, rather frantic arrangement (bass and keyboards responding to each other in a wild race. It was therefore a matter of democratizing this unsettling piece of music, whose opening words are a perfect introduction: "Stories came like the wind...".

Big Sleep : This track is taken from the album New Gold Dream, which happens to be when these young Stakhanovists (six albums in four years) started writing real songs illuminating their twilight sound. I thought it would be interesting to strip the song of its early '80s trappings (synthesizer, slapping bass, drums drowned in reverb) and extract its most timeless components.

Up On The Catwalk : A track from a period of transition for Simple Minds, as the club band gives way to the stadium band. Producer Steve Lillywhite emphasized their sound to bring about this mutation. Yet I have always sensed something nostalgic, almost tragic, in this song, hidden behind its energetic sound, which I have tried to put the stress on in this pared-down arrangement.

Wonderful In Young Life : As with 20th Century Promised Land, this song isn't often referred to, even by “hardcore” fans. I love the break between its verses, rough and brutal and its intriguing, hypnotic chorus. In Orwell's own version, a Carole King-influenced piano has become the matrix for a track that humbly ogles to late '70s Bowie productions.

Speed Your Love To Me : The original recording of this cover dates from 2010, but a few brushstrokes have been added since, starting with young Anthéa Faure-Pouget’s translucent voice, which reinforces the song's airy dimension.

Seeing Out The Angel : The original version is slow, contemplative, elegiac and uncompromising. In Orwell's version, the strings of the acoustic guitars, violins, cello and double bass have replaced the electrified instruments, once again to underline the fact that this goes beyond fashion trends. In fact, Simple Minds used it as the basis for their 1988 hit, Mandela Day. But Seeing Out The Angel is far more original in my eyes.